ARTISTS’ ROADS

LE VIE DEGLI ARTISTI

watch the videos at the bottom of the page!

TARZO

Tarzo: Colour and Sound, The Shapes of Memory

Every civilisation has produced great works of art so that future generations might know the lives, hopes, and sorrows of those who once lived in a place.

Before books or films ever existed, it was painting that fed the desire to tell stories.

Panels and canvases have long served this purpose.

But before them came the walls.

Of caves, of houses, and of churches.

In 2008, in the hamlets of Fratta and Colmaggiore, two villages overlooking the lakes of Revine Lago and Tarzo, people became aware of an inescapable reality.

These were no longer the villages of a hundred, or even fifty, years ago. The farming world had vanished, swept away by the rush of modern life.

True, the houses, the streets, the fountains and footpaths were still there, but they were becoming silent spaces.

The people, the trades, the smells and the sounds had disappeared.

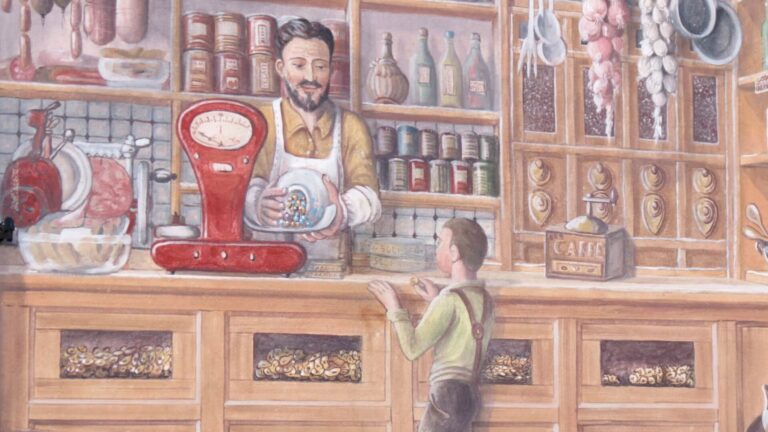

And so the “Via dei Murales” was born, bringing together thirteen artists to fill the streets with colour. It’s as if the walls had melted away, revealing the life once lived in that home, that courtyard, that workshop.

Mural painting may have its roots in Latin America, but it has found fertile ground in Italy too. From the dreamlike murals of Dozza, to the politically charged walls of Orgosolo, to the poetic images of Cibiana di Cadore.

To truly appreciate these works, one must walk with “slow and quiet steps.” They cannot be glimpsed from a car window.

The images gradually reveal themselves, flling today’s silence with the echoes of yesterday’s sounds.

We discover traditional crafts still practiced, albeit with the tools of modernity.

Others have disappeared altogether: felling a woodland is no easy task. It must be done with skill, so that other trees may grow. One had to know how to gather and bind slender marsh reeds to make woven mats, called grisioe here. One had to know how to knead and shape clay to make roof tiles of just the right thickness and proper curvature. One had to know every step in rearing silkworms to keep this delicate moth alive, feeding it mulberry leaves and sheltering it with warmth or cool depending on its life cycle.

Our civilisation knows everything but it cannot do everything.

We must also speak of painful things like emigration, a harsh reality for this land from the mid-1800s to the end of the Second World War.

Then came sharecropping which forced families to leave their meagre land on Saint Martin’s Day, the eleventh of November, and chestnuts, which were once a precious staple food.

But there is also chatter by the fountain or a family gathered in front of their home, where no one is idle.

The mother knits, someone winds wool into balls, someone sweeps, someone tidies the house, another cares for the little ones, another returns from the vegetable garden.

Later, as night draws in, they’ll tell the children tales of the mazariol.

Not far away, through the rows of osiers by the lake, a small boat drifts silently. Two young lovers, hidden by the dark and lit by the stars, have slipped free from their parents’ watchful gaze to draw close to one another.

A beautiful idea, these murals and perhaps without realising it, they’ve placed themselves in the wake of a long tradition.

For among these hills are churches that preserve remarkable frescoes, like the fifteenth-century paintings in the Church of San Martino in Fratta. And nearby, there now stands a mural of the saint himself like the sinopia beneath an ancient painting.

MORE EXPERIENCES!

L’Arte racconta la civiltà del passato:

- Il Cristo della Domenica nella pieve di San Pietro di Felletto

- A Follina, il chiostro è il luogo della vita

- Cave e cavatori: il campanile di Fregona

- Un assaggio di preistoria al Livelet

MULTIMEDIAL MAP: “ARTISTS’ ROADS – LE VIE DEGLI ARTISTI- EN”!